Brooms vs Vacuums: When to use an ORM

One rather frustrating topic issue that I’ve encountered as a software engineer is the groupthink around using an Object-Relational Mapper (ORM). Some people don’t understand the tradeoffs of using an ORM, vs writing data access code by hand. As a result, they can’t comprehend why someone would write their own queries or populate their own objects.

To summarize the tradeoffs:

- Hand-written SQL and manual creation of objects: This approach can get quite time-consuming and tedious. It also might require learning arcane database syntax, or significant rewrites if the database vendor changes. In contrast, hand-written queries normally run faster than queries from an ORM, and the application will use less CPU and RAM.

- ORM: Often, it is much faster (developer time) to use an ORM, but getting high performance can require tedious optimization or learning many more details about the ORM than the actual database. Often, if the database vendor changes, the ORM can adapt to a new database with minimal changes to application queries or mappings. Introducing an ORM to a project with a very simple schema may be more time consuming than writing queries by hand, due to complications importing 3rd party dependencies.

The best way to think through the tradeoffs is to ask yourself: Do you need a broom or a vacuum?

When to use a broom vs a vacuum?

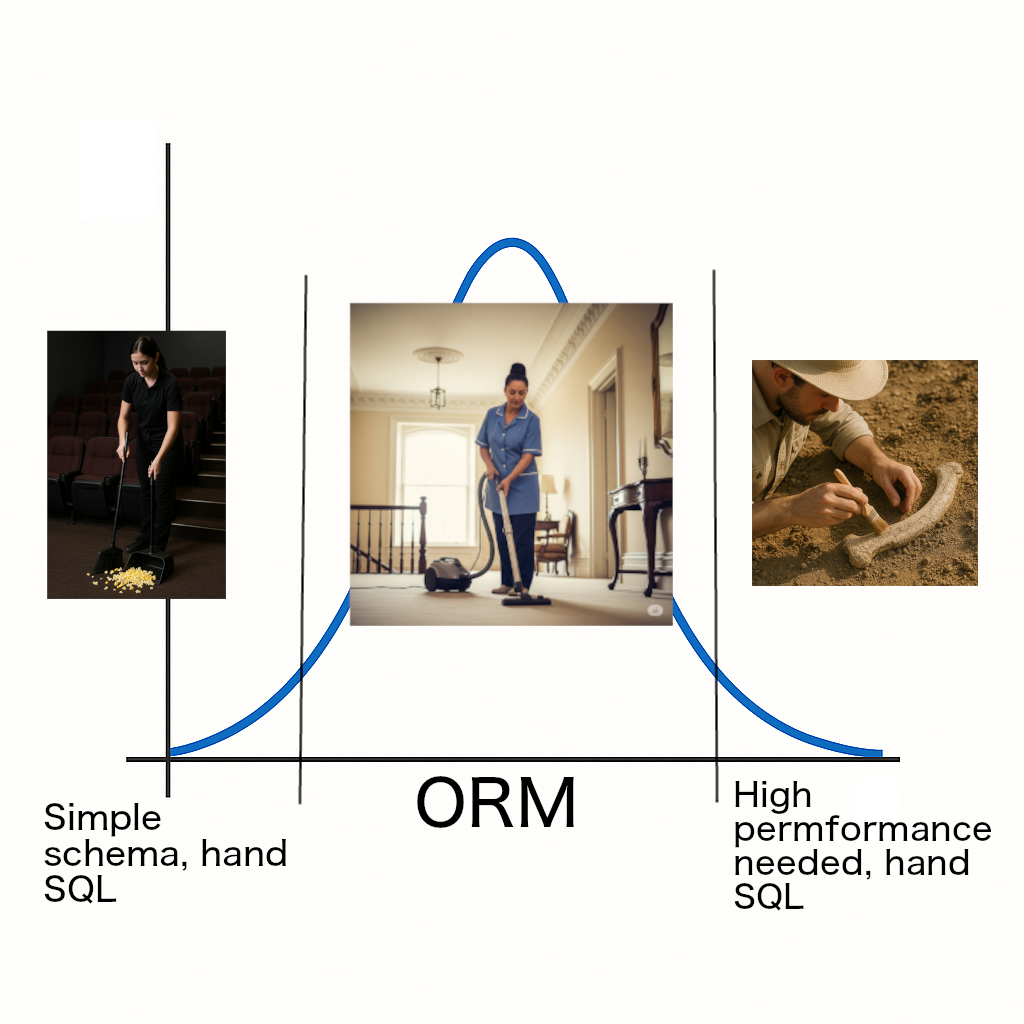

Think about where you live: You probably vacuum once a week or so, or you might even pay housekeepers, who vacuum your home for you. But, if you spill some dirt or food, will you use a vacuum to clean the mess every time? Let’s think through the decision about which tool to use for a mess:

- Weight: A broom weighs much less than a vacuum. Do you want to lug the vacuum to the mess?

- Cord management: A broom doesn’t require electricity. Do you want to take the time to plug the vacuum in? And yes, there are cordless vacuums. I used to own one. But this leads to the next point…

- …Reliability: A vacuum is more likely to break in a way that a broom doesn’t. My cordless vacuum broke twice on me. I haven’t had a broom break in a way that it couldn’t be used.

- Size of mess: Did you spill a small amount of dirt, or food?

You might think, “Is it worth it to lug out the vacuum, plug it in, and hope that it’s not broken?” Certainly, if it’s a big mess, it’s worth it. But for a small mess, it’s not. You’ll take out a broom and a dustpan, sweep it up in one or two motions, empty the dustpan into the trash, and be done. You could choose to buy a small hand vacuum, but once it breaks, you’ll find that it takes more time to futz with the hand vacuum instead of just using a damn broom.

But what if your housekeepers chose to bring brooms instead of vacuums? If you’re home while they broom your house, you might appreciate the quiet; but if you have carpets, or a large house, brooming instead of vacuuming might not be practical.

Don’t assume that “brooms are for small messes, vacuums are professionals.” I can think of some cases where a professional will choose a broom:

- The staff at a movie theater may use a lobby broom and dustpan to clean up popcorn between shows.

- An archeologist will use a soft-bristle brush to remove dust and dirt from an artifact.

Deciding to use an ORM or writing queries by hand

Choosing to write your own queries by hand, or using an ORM, simply requires understanding your needs.

When I worked at Syncplicity, we decided to refactor the desktop client to use SQLite without an ORM. Initially, this decision was mildly controversial: When I joined the company, the desktop client used a very early version of NHibernate; but it performed poorly because it used NHibernate incorrectly.

I pointed out to my team members some important facts:

- We had so few tables in our schema, and so few queries, that learning to use NHibernate correctly would take more time then just writing some queries by hand.

- All newcomers to our team would need to invest time in learning how to use NHibernate

- NHibernate’s binary was many times larger than our binary

The problem that Syncplicity had with NHibernate was that the desktop client treated its SQLite database as a large, in-memory data structure. This is not how databases, and thus ORMs, are designed to work! As a consequence, the Syncplicity Desktop client performed very poorly whenever it used the database. This was not NHibernate’s fault, as their documentation explicitly stated not to use it to treat a database as a large, in-memory data structure. The problem was that, in order to use the database correctly, everyone had to first learn how to program with a database, and then learn how to use NHibernate correctly. The challenge with NHibernate (and most ORMs in general) is that it takes more time to learn how to use the ORM correctly than it takes to write a handful of simple database queries. (And, remember that you still need to know how to program with a database in order to use an ORM. You can’t just introduce an ORM to a product as a replacement for requiring that your engineers know how to use a database.)

The decision to remove NHibernate was correct: Later, newcomers to the team appreciated that we had a small amount of very simple database code that was easy to learn, and easy to maintain. As we went through acquisitions, we didn’t need to “defend” NHibernate to each parent company’s legal team. (Each company that acquired us did its due diligence and audited our 3rd party dependencies) We also didn’t need to worry about NHibernate’s security vulnerabilities. We never switched from SQLite to another database, but if we did, there was so little “database” code that rewriting it wouldn’t have taken a lot of time. (And finally, our application size was significantly smaller.)

It would be a different case if the Syncplicity Desktop client had a more complicated schema and/or made significantly more database queries. In that case, the learning curve, and the implicit cost of a 3rd party library, would have been “worth it.”

After Syncplicity, I joined OptiRTC. Our backend service probably has in excess of 100 tables, and there are probably at least 1000, if not more, queries. We also run a lot of ad-hoc queries using LINQPad. In our case, we use Entity Framework. Writing queries “by hand”, except in performance critical areas, is a “fools errand” for us due to our team size.

Entity Framework, with LINQPad, allows us to more easily write ad-hoc queries, and read the data, than we could using a traditional SQL console. Even if all application code used hand-written SQL, it would be “worth it” for us to create Entity Framework bindings merely to support LINQPad.

We do have some older code, written by junior programmers, that is sensitive to cartesian explosion. This is a consequence of junior programmers not understanding the limits of ORMs in database programming.

In contrast to OptiRTC, a few years ago, one weekend I quickly made a proof-of-concept web application with a database. It had one or two tables, and a few queries. I believed that it would take me more time to set up Entity Framework than to just write queries by hand, so that’s what I did. Nothing ever came out of the weekend proof-of-concept; but if it did turn into a larger project, I would have included Entity Framework.

It’s not hard to write SQL queries by hand

… it’s just time consuming to construct and populate your data structures!

SQL is a very simple language: Any competent programmer can learn to write basic CRUD queries. Joins and aggregations are also techniques that any competent programmer can learn. Writing the corresponding data structures and population logic that uses a data reader is also basic programming; any programmer who can solve Fizzbuzz or pass a basic data structures class should be able to do this.

The issue is that this is time consuming code to write! Using Entity Framework, I can write a query with complicated joins, and get back fully-populated objects, in a matter of minutes. A query with complicated joins, when written by hand, and when the objects are populated by hand, can take hours, if not longer, to implement.

The difference is in optimization, debugging, and working around bugs in 3rd party libraries. Much like how a vacuum can malfunction in ways that a broom never will, an ORM can malfunction in ways that hand-written SQL and hand-written object population code will never malfunction. When implementing a complicated application with lots of tables, relationships, and queries, an ORM will save significant time. In contrast, using a broom, IE, writing queries by hand, is mostly only “worth it” when setting up and learning to use the ORM correctly takes more time than writing the query, or for queries with significant performance needs.

When using a database, do you need a broom or a vacuum?

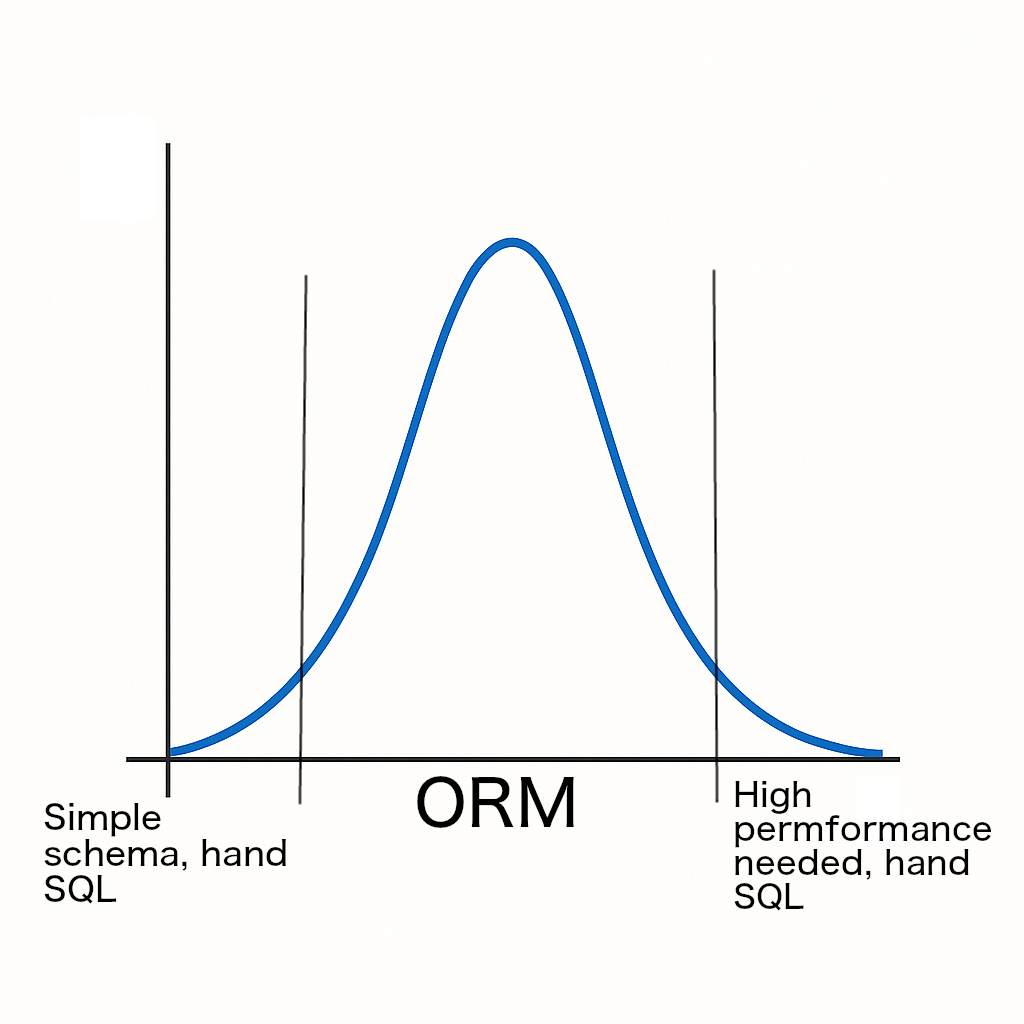

When deciding between an ORM or hand-written queries, I like to think of three categories:

- Broom because of simplicity: The database has few tables and simple query needs. I will skip the ORM because I’ll never “break even” on the time it takes to set it up and learn how to use it correctly.

- Vacuum because of breadth: The database had many tables and queries. I will “break even” on the time it takes to pick an ORM, set it up, learn how to use it correctly, work around its bugs, react to its security vulnerabilities, and defend its license to the company’s legal team.

- Archeologist’s paintbrush because of specialization: The application has “hot” queries, is performance sensitive, or otherwise needs every kind of performance boost it can get. In this case, it’s “worth it” to invest the time and or manpower into hand-writing optimized queries and code to populate objects.

Appendix: The Tragedy of VMWare’s Capacity Planner rewrite

In 2007, I joined VMware to work on the Capacity Planner tool. We were rewriting it in C# with NHibernate as the ORM around the Firebird database. The project ultimately was a failure, and never shipped.

The primary cause of the failure was a belief that an ORM, like NHibernate, was enough to compensate for developers not knowing how to use a database, or to even think about the correct design patterns to use when programming with a database. Internally, the Capacity Planner tool treated the database, through NHibernate, as a large in-memory data structure. It performed very poorly, primarily because it encountered the N+1 problem.

The Capacity Planner had a very simple database schema, about 10 tables if I remember correctly. It was simple enough that a broom (no ORM) could have been enough. Instead of recognizing and fixing the problem, (either by writing queries by hand or learning to use NHibernate correctly), the team decided to implement a complicated scalability layer and “scale out” the tool. This added significant development complexity, and if the tool ever shipped, significant deployment complexity.

To rephrase, the “scale out” approach the team took to the performance problems was significantly more complicated than simply optimizing the Capacity Planner’s data access layer.

This mistake was made before I joined the team, yet it took me some time to understand the problem. At the time, I was early in my career and trying to learn from people who I believed were more experienced than me.

After I was on the team for about a year, I encountered a problem. One day, while testing, the Capacity Planner became so bogged down that my hard drive started clicking like crazy. (This was 2008 when we still had mechanical hard drives.) There were probably only a few thousand rows in the database, so this behavior was unexpected, and obviously incorrect.

The next day I spent some time researching how to use NHibernate correctly, and realized that:

- The way we were using it, as a large, in-memory data structure, was incorrect.

- NHibernate was way too complicated of a tool to use with such a simple schema.

I tried to discuss this with the team’s architect, but he told me that, to paraphrase, “ORMs are the modern way to use a database, and we shouldn’t have to think about the database.”

It then became clear why the Capacity Planner project failed:

- The team leadership believed that ORMs were a replacement for knowing how to program a database. (They are a tool for people who already know how to use a database, and have their own learning curve.)

- The Capacity Planner had unprofessionally poor performance because the lead developers (before I arrived) did not know how to program with a database.

- The team tried to compensate with an ambitious “scale out” approach.

- The “scale out” approach was more complicated, fragile, and time consuming than merely learning how to use a database, and either write the queries by hand, or learn how to use NHibernate correctly.

Instead, had the leadership taken the “broom vs vacuum” philosophy, they would have started “at day one” requiring that the team members learn how to program with a database correctly. They also would have made an informed decision about if NHibernate was really needed, because the schema itself was so simple that it was hard to justify that added overhead of an ORM.